NASA's Curiosity rover has found some interesting organic compounds on the Red Planet that could be signs of ancient Mars life, but it will take a lot more work to test that hypothesis.

Some of the powdered rock samples that Curiosity has collected over the years contain organics rich in a type of carbon that here on Earth is associated with life, researchers report in a new study.

But Mars is very different from our world, and many Martian processes remain mysterious. So it's too early to know what generated the intriguing chemicals, study team members stressed.

"We're finding things on Mars that are tantalizingly interesting, but we would really need more evidence to say we've identified life," Paul Mahaffy, who served as the principal investigator of Curiosity's Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) chemistry lab until retiring from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, in December 2021, said in a statement. "So we're looking at what else could have caused the carbon signature we're seeing, if not life."

Nearly a decade of sample analysis

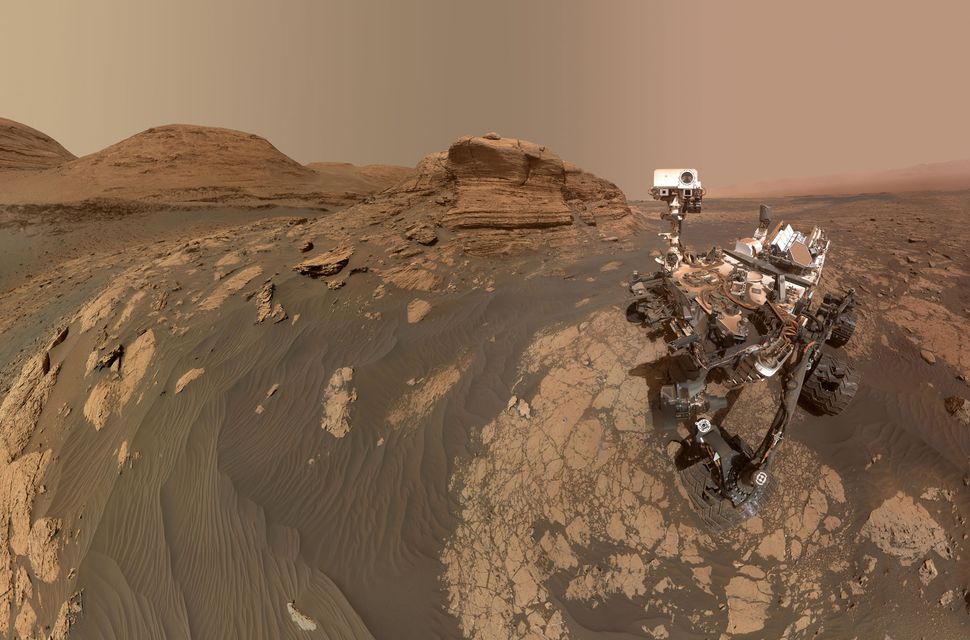

Curiosity landed inside Mars' 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater in August 2012 on a mission to determine if the area could ever have supported microbial life. The rover team soon determined that Gale's floor was a potentially habitable environment billions of years ago, harboring a lake-and-stream system that likely persisted for millions of years at a time.

In the new study, which will be published Tuesday (Jan. 18) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research team looked at two dozen powdered rock samples that Curiosity collected with its percussive drill from a variety of locations between August 2012 and July 2021. The rover fed this material into SAM, which can identify and characterize organics — carbon-containing molecules that are the building blocks of life on Earth.

The scientists found that nearly half of these samples were enriched in carbon-12, the lighter of the two stable carbon isotopes, compared to previous measurements of Mars meteorites and the Martian atmosphere. (Isotopes are versions of an element that contain different numbers of neutrons in their atomic nuclei. Carbon-12 has six neutrons, and the far less abundant carbon-13 has seven.)

These high-carbon-12 samples came from five different locations within Gale Crater, all of which featured ancient surfaces that had been preserved well over the eons.

On Earth, organisms preferentially use carbon-12 for their metabolic processes, so enrichment in this isotope in ancient rock samples here is generally interpreted as a signal of biotic chemistry. But carbon cycles on Mars aren't understood nearly well enough to make similar assumptions for Red Planet finds, study team members said.

The researchers came up with three possible explanations for the intriguing carbon signal. The first involves Mars microbes producing methane, which was then converted into more complex organic molecules after interacting with ultraviolet (UV) light in the Red Planet air. These larger organics then fell back to the ground and were incorporated into the rocks that Curiosity sampled.

But similar reactions involving UV light and non-biological carbon dioxide, by far the most abundant gas in Mars' atmosphere, could have generated the result as well. It's also possible that the solar system drifted through a giant molecular cloud rich in carbon-12 long ago, the researchers said.

"All three explanations fit the data," study leader Christopher House, a Curiosity scientist based at Penn State University, said in the same statement. "We simply need more data to rule them in or out."

Comments

Post a Comment